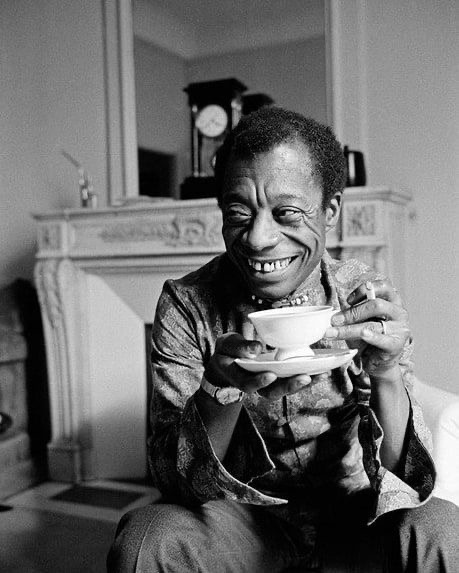

STOCKTON: Thinking of the major figures of the civil rights movement, who usually comes to mind? Generally speaking, I’d say people like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, and maybe even Thurgood Marshall, for all you history buffs out there. Hardly ever, if at all, is James Baldwin thought of, let alone mentioned and talked about in our high school classes. That’s not to say that he’s a total nobody of course. After all, a whole documentary was made about the man in 2016, inspired by one of his unfinished memoirs. One of Baldwin’s novels, If Beale Street Could Talk, was also adapted into film two years later in 2018. Both the documentary and the movie adaptation went on to be nominated at the Oscars, so it’s not as if Baldwin’s life and work is cloaked and shrouded in total mystery. That being said, Baldwin is virtually unknown among young Americans. Shameful as that is, his relatively unknown and underappreciated status only belies how great the man was. Taking this into account, not to mention the fact that Black History Month was only last month, has prompted me to honor Baldwin by opening people’s eyes to what he thought about love. But why focus on love? Well, apart from Valentine’s Day having passed just a couple of weeks ago, if I were to identify one unifying theme or force that animated Baldwin—as writer, orator, activist—it would be love. But first, who was the man?

James Baldwin’s story begins in Harlem, New York, where he was born to Maryland native Emma Berdis Jones on August 2, 1924. Having given birth out of wedlock, she would eventually marry David Baldwin—a Baptist minister who had recently migrated north from New Orleans—when James was still a baby. James would never discover who his biological father was. The elder Baldwin was a reportedly strict man, who would often quarrel with the young James. David Baldwin was also noted by his son to harbor strong resentment toward White people and would often cry out that they’d be condemned for their sins. Suffice it to say that the relationship between Baldwin the elder and Baldwin the younger was a complicated one that would have profound implications for the kind of man the latter grew up to be. In his teenage years, James Baldwin would also become a preacher for the Pentecostal Church. He admitted in later life that this experience was a way to grapple with and repress his burgeoning homosexuality, which he’d come to embrace by adulthood. Baldwin recounts both this and his relationship with his father in great detail and candor in his essay Down at the Cross. As for how James Baldwin became a writer, he took up reading at an early age, tackling authors from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Charles Dickens when his age hadn’t even reached double digits yet. At the same time, the young James started to dabble in writing poetry and plays, definitively setting his life’s trajectory toward the arts. Needless to say, he was precocious and wise beyond his years, which his teachers were quick to recognize. He befriended kids of all different races and had both black and white teachers, one of whom, Bill Miller, he’d cite as the reason why he never came to hate White people, in stark contrast to his father. Following his graduation from high school, Baldwin moved down to Greenwich Village, regarded as the hub of the New York avant-garde. This allowed him to pursue a literary apprenticeship that resulted in a few book reviews of his being published in some local journals and magazines. The turning point in Baldwin’s writing career would be his meeting with Richard Wright, known as the author of Native Son and Black Boy, who made the publication of Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, financially possible. Seeking to flee from the racism and homophobia rampant in America at that time, Baldwin moved to France in 1948. It was during this time that he finished writing and published two of his biggest novels: the above-mentioned Go Tell It on the Mountain in 1953 and Giovanni’s Room in 1956. It was also around this time that he began attacking Richard Wright, the same one who sponsored him and served as his mentor, which culminated in the publication of his well-regarded Notes of a Native Son. To get himself involved first-hand in the civil rights movement, Baldwin would return to the United States in 1957. Throughout this time, he became friends with Martin Luther King Jr., Medgar Evans, and Malcolm X, whom he’d debate in 1961. Baldwin was also a leading participant in the famous 1963 March on Washington. Two years later in 1965, he got involved in the Selma March in Alabama that was also led by Dr. King. In the 70s and 80s, the last two decades of his life, he would divide his time between France, Switzerland, and Turkey. Baldwin would also give lectures from time to time at various American universities and colleges, including UC Berkeley and UMass Amherst. He published his two final novels If Beale Street Could Talk in 1974, and Just Above My Head in 1979. At age 62, he was inducted into the Legion of Honor, the highest order of merit in France. Baldwin succumbed to stomach cancer on December 1, 1987, aged 63, leaving behind an immense legacy in both civil rights and in literature. So that’s Baldwin’s life in a nutshell.

But what did love mean to James Baldwin? For starters, the kind of love that Baldwin professed had nothing to do with the kind of love you see in a soap opera. That’s to say that there was nothing even remotely transactional about Baldwin’s love; it was all about obligations and about what we owe to each other. His love was concerned first and foremost with race relations at the height of the struggle for civil rights. His love dealt with the problem of desegregation, and to be more precise: integration. Some good adjectives that capture his treatment of love include transformative, passionate, vulnerable, searing hot—love as it is, love in its purest form, free of anything banal and vapid. But to really understand Baldwin’s conception of love, it’s imperative that we first understand what Baldwin meant by a system of reality. He used this idea to lay bare the situation of many White Americans in his time. So what is it exactly? We can look to his famous 1965 Cambridge Union debate with William F. Buckley Jr. for an answer. Arguing for the proposition that the American Dream is at the expense of the American Negro, Baldwin began making his case by noting that, whether one accepts or rejects the premise for which he is arguing, it all really comes down to “where you find yourself in the world, what your sense of reality is, [and] what your system of reality is.” Adding that it’s those “assumption[s] which we hold so deeply so as to be scarcely aware of them” that determine one’s reply to that question. According to Baldwin, in the case of many White Americans at that time, their system of reality was anchored to racial supremacy. To put it another way, their identity and sense of worth rested on their insistence that they were the supreme race, and that those subordinate to them—people of color, Black people in particular—ought to be at their utter mercy. In political terms, this meant the preservation of Jim Crow segregation. Baldwin further explains this concept of a system of reality in My Dungeon Shook—an open letter he wrote to his nephew of the same name—where he likens Black Americans’ existence in the imagination of many White Americans to “a fixed star”, such that any upheaval to the prevailing state of affairs would be virtually the same as waking up “to find the sun shining and all the stars aflame.” In his essay Faulkner and Desegregation, Baldwin in a rather pithy way summarizes the anguish the White American psyche has endured, writing that “[a]ny real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it”—in short—“the end of safety.”

Recognizing integration’s political and psychological ramifications, he exhorts his namesake in My Dungeon Shook to accept White people with love, owing to them being “trapped in a history which they do not understand.” That right there is the heart of Baldwin, the essence of his love. It has everything to do with exercising compassion and empathy, that is, exercising one’s humanity. Acknowledging that this country’s history tells a story of an evil with innumerable dimensions and of an unparalleled magnitude, Baldwin urges us to answer this: how must we countrymen move beyond America’s troubled past? To where we can forge a future in which America realizes the dream it ostensibly provides, the destiny it must so desperately achieve? Baldwin’s political project was therefore one of reconciliation. But what does this reconciliation call for? Solidarity and healing, which in turn call for cooperation among Americans and the dismantling of certain institutions that place one stratum of people subservient to another. As Baldwin declares, “we live in an age which silence is not only criminal but suicidal.” Thus, far from being this conciliatory figure who’d peddle feel-good platitudes, Baldwin was fully committed to cleanse this country of the legacy of its greatest sin: slavery. As a genuine radical, Baldwin sought to root out racism in all of its manifestations, whether it be political or psychological. He strived to make “America what America must become.”

My preview of Baldwin is just that—a preview. It can only go so far. That being the case, I encourage everybody to at least read The Fire Next Time, for it encapsulates the best of Baldwin’s writing and offers anybody who’s curious a thorough contextualization of why he stood for what he stood for. If anything, the one thing I’d like for people to get from out of my paean to Baldwin is to read the man themselves. Baldwin above all else wanted to be, in his own words, “an honest man and a good writer.” In that spirit, we all ought to live a life with conviction and fervor, true to ourselves and devotees to the cause of humanity.

Baldwin is dead, long live Baldwin!